The 1918 Influenza Won't Help Us Navigate This Pandemic - The Atlantic

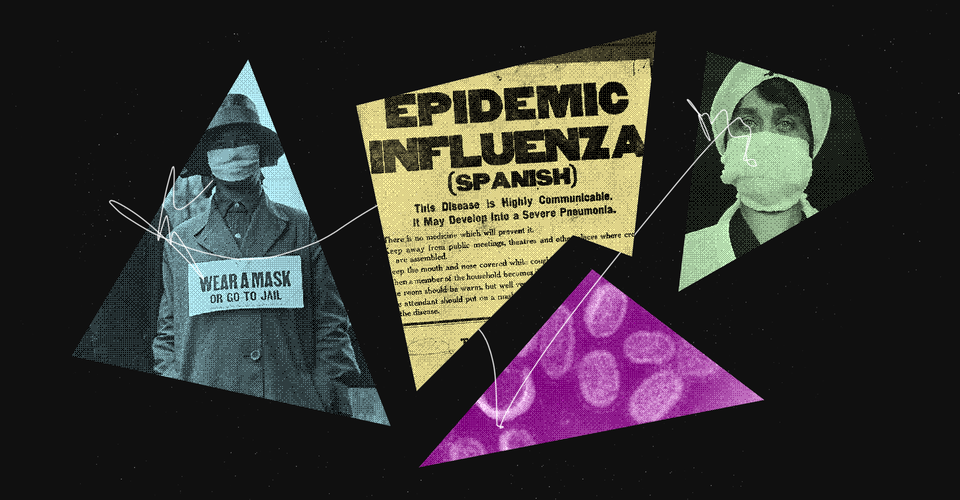

As a medical historian, I have never been busier. Over the past 20 months, journalists and policy makers have reached out in an effort to understand what past infectious diseases might teach us about this one. These exchanges almost always end with questions about how this pandemic is similar to the influenza pandemic of 1918–19, which, until COVID-19, was the worst pandemic in human history.

The truth is we have no historical precedent for the moment we're in now. We need to stop thinking back to 1918 as a guide for how to act in the present and to start thinking forward from 2021 as a guide to how to act in the future. This is the pandemic I will be studying and teaching to the next generation of doctors and public-health students.

Some similarities exist between now and 1918—the economic costs of quarantine and the fears that each virus inspired worldwide, for example. And before the Delta variant came along, when everyone was looking forward to a "hot vax summer," traveling again, and returning to the office, I'd hoped that we might be heading to normalcy, and perhaps even to a boom similar to that of the 1920s. The influenza epidemic (along with the close of World War I) contributed to Warren G. Harding's 1920 presidential-campaign slogan, "normal times and a return to normalcy." Harding presided over what F. Scott Fitzgerald famously named the Jazz Age, a time when, as Fitzgerald wrote in The Crack-Up, "the uncertainties of 1919 were over—there seemed to be little doubt about what was going to happen—America was going on the greatest, gaudiest spree in history and there was going to be plenty to tell about it."

But the past few weeks have robbed me of that thought. I cannot seriously believe that, in our socially damaged and ideologically splintered world, we have a chance at a new Roaring '20s, a renaissance of culture and lucre.

The differences between the pandemics outweigh the similarities. In terms of raw numbers, COVID-19 has sickened more people than the 1918–19 influenza pandemic did, even though demographic purists might object and ask to account for the smaller global population in 1918 and the relative youth of many of the influenza's victims. Influenza appears to have killed approximately 500,000 to 650,000 Americans; the estimates of deaths worldwide begin at about 20 million but go as high as 100 million. As of August 18, 2021, the recorded global caseload of COVID-19 was more than 208 million, the recorded death rate in the U.S. was more than 623,000, and at least 4.3 million worldwide have died.

Such startling statistics come as the more contagious Delta variant continues to fan an inferno that has never stopped consuming oxygen. In other words, this pandemic is far from over. In all of recorded history, the world hasn't really halted as abruptly as it did for most of us during the past year or so. In 1918, social-distancing orders were adopted for far shorter periods of time (on average, about 10 weeks), compared with our year-and-a-half-long coronavirus endurance test. And finally, our distrust of one another seems unparalleled, as masks and vaccines have become more about political choices than public-health concerns.

Over the past two decades, I have written several books and hundreds of scholarly papers on how pandemics create fear of the unknown. I've studied this fear, and yet even I have fallen prey to it during the pandemic. Recently, I took a walk around my neighborhood. I made sure to wear a face mask, even though I was immunized with the Pfizer vaccine in January. I slowed my gait to stay six feet away from other pedestrians, many of whom I knew and who were trying to do the same for me. Looking at people headed in my direction, I could sense their fear of invisible virions that I may or may not have expelled from my lungs. And then I was alarmed to realize that I was thinking ill of them. What if they were those people who refused to be vaccinated but, nonetheless, refused to wear a face mask?

For the past 75 years, the wealthier nations of the world have enjoyed a reprieve from most infectious diseases—largely thanks to robust mass-vaccination and public-health programs. But in this century alone, we have already experienced six contagious crises (SARS in 2003; H1N5 avian influenza in 2005–06; H1N1 influenza in 2009; MERS in 2012; Ebola in 2014; and COVID-19). Our post-COVID-19 world—if we ever get there—will likely feature successive, emerging, and reemerging infectious threats. Extreme climate change may bring about a whole new microbial world rife with threats to the human population. Rapid international jet travel, a growing anti-vaxxer movement, antibiotic resistance, and zoonotic jumps of viruses from one species to another only accelerate this danger.

To manage that future, I won't look to our past; I'll look to how we handle our present. We must learn to innovate, plan, and test evidence-based pandemic protocols; develop and resupply stockpiles of protective gear, intensive-care devices, medications, and vaccines; and fund basic infectious-disease research. We must also insist that our leaders demand transparent communication and disease surveillance among all nations as new threats develop around the world.

Citizens, too, have a responsibility to tell their leaders they want sound, science-based public-health policies to protect them. Most of us are happy to pay taxes supporting our local fire department even if the odds of our own home burning down are small. In the event of such a disaster, we have confidence that the firefighters will come to extinguish the blaze before it is too late. The same federal financial support must be applied to funding our public-health agencies and for our citizens who are experiencing food, housing, or income insecurity.

What keeps me awake at night is the real risk that our flummoxed leaders will forget about the very issues that got us into this mess in the first place. They will move on to other projects and plans. Such purposeful amnesia only helps to set us up for another pandemic—a tragedy of Himalayan proportions, not to mention a definite threat to our collective health. The coronavirus pandemic is setting a new benchmark, one we'll be studying to help us navigate the next one.

Comments

Post a Comment